A trillion-dollar carbon removal market?

Musings on a recent debate and whether we're crazy to believe the world would ever pay that much for carbon removal

So far I’ve been writing about what it will take to get to a healthy, thriving, and huge permanent carbon removal market—maybe the single most important market creation and market shaping challenge humanity will tackle this century. I’ve used the trillion-dollar threshold as a super rough placeholder for mid-century market size (give or take some hundreds of billions, or 5-10 years in the ramp-up timeframe). But is a market that big just a pipe dream? Is all the investment going into carbon removal businesses just private sector folly?

About a month ago, Michael Liebreich put out a great podcast episode with Julio Friedmann (the “Carbon Wrangler”) of Carbon Direct. Toward the end of their conversation, they got talking about whether it is believable that the world will spend $200B per year on carbon removal decades from now. The Carbon Wrangler argued that it’s eminently plausible. Liebreich, channeling Vaclav Smil’s skepticism, took a strong position that he can’t see it happening. He also implied that it’s counter-productive for people to be bandying about the notion of gigaton-scale procurement of $100/ton carbon removal when pursuing a fool’s errand will steal scarce funding, talent, and political attention from the main events of emissions reduction and adaptation. And some subsequent Twitter exchanges (since deleted) characterized anyone working on or investing in permanent carbon removal as effectively doing charity work.

At one level, it can feel super abstract or academic to be speculating in 2022 about what’s likely in 2040 or 2050. If we’re honest, who the hell really knows? Will Tom Brady still be a starting quarterback at age 67? If we rewind to 1995 would anyone have believed where we’d be now with solar or with EVs? We need to bring some intellectual humility to questions like these. And I don’t bring much to the speculation party; I’m not a political scientist or a carbon removal techno-economic analysis ninja or a macroeconomist.

But—and this is a pretty big but—if we have reason to be very confident that the demand will never materialize for a gigaton-scale carbon removal market, that should stop a lot of current activity in its tracks. What follows is some quick-and-dirty reasoning as to why a market that big is far from a crazy notion.

What’s the right thought exercise?

So the conversation about plausible future market size is a very important one, even with all the caveats. But if we’re going to engage it, it’s important that we frame it up well and see the question(s) with clear eyes even when the future is opaque. There’s still a lot of muddle in our public dialogue about carbon removal. People often mistakenly equate permanent carbon removal with direct air capture (DAC), or conflate carbon removal with carbon capture for emissions reduction purposes. Even the sophisticated Liebreich / Friedmann discussion had many moments of treating carbon removal and DAC interchangeably, as if the vast majority of the $200B hypothetical future market they were debating would be a DAC market.

To make the question we’re wrestling with more precise, let’s posit a few things:

We’re talking about high-durability forms of carbon removal—and in a tech-agnostic way that includes many more technologies than just DAC

As we evaluate how plausible it is that market size could reach a certain level, we’re setting aside for now the question of supply scale-up and focusing specifically on aggregate demand

We’re specifically asking about demand and market size by mid-century—say, 2050 give or take 5-10 years—not by late-century or “any point in the future”

We should be contemplating the plausibility of a market size even bigger than the $200B number in the Liebreich / Friedmann debate

How big a number should we be considering? The $200B number was premised on a thought exercise of roughly two gigatons annually being sold at an average price of $100/ton. But we shouldn’t get too fixated on either that volume or that price. Considering plausible ranges for each1, we could be contemplating a required market size anywhere from the low hundreds-of-billions zone (say 2-5 gigatons in the $50-100/ton range) up to a $1 or 2 trillion level (>10+ gigatons at >$100/ton) as a frame. Just for the purposes of this piece, let’s think about the middle of that spectrum – high hundreds of billions or $1 trillion.

How believable is that rough level of mid-century market size?

In considering this question there are at least a few important lenses to look through and things to bear in mind.

Useful analogies

Drawing on analogies was the primary analytical angle in the Liebreich / Friedmann debate. Liebreich doesn’t believe we’ll be willing to spend huge dollars on carbon removal given that it yields purely public benefits that feel more invisible, diffuse or distant—not immediately tangible to any individual. Responding to that line of skepticism, the Carbon Wrangler pointed to trash disposal and vaccines as analogies, given that they also produce largely invisible or diffuse benefits and yet the benefits are so real that governments (collectively) are willing to spend billions on both.2

Are trash disposal or vaccines the right analogy? They’re at least in the right zone. Yet for any one person, the leap of imagination for ‘how does this benefit me or my immediate community?’ seems a good deal smaller for trash disposal or vaccines than for carbon removal. Yes, vaccines can provide invisible herd immunity and I never directly experience the avoided infection, but at least that shot in my arm is helping me in a way I can grok. And if no-one takes my trash away, my neighborhood will stink and have rats and piles of trash. If I’m an average citizen by mid-century, maybe I’ve heard talking heads chatter about carbon removal—but I may not feel a very palpable connection between carbon removal and my region experiencing more or less heat or drought or flooding or wildfires than is already happening at the baseline level I’ve become disturbingly accustomed to.

If trash and vaccines are helpful but imperfect analogies, what do we spend hundreds of billions of dollars on that produces benefits as invisible or diffuse to most people as carbon removal? Development aid—referred to as Official Development Assistance (ODA)—from wealthy countries to low- and middle-income countries is one particularly good example. I touch on the origins of ODA further below. ODA has become a complex set of aid flows, with some going direct from government to government (sometimes channeled via UN or other “multilateral” organizations) but much of it being channeled through NGOs and private contractors who implement programs and deliver services in developing countries.3

Similar to what we might imagine for carbon removal by mid-century, many people living in wealthy countries have some broad-brushstrokes understanding of what development aid does and why (up to a point) it’s a reasonable use of government funds. It rarely crosses their mind because they don’t feel it affecting their life tangibly, but despite that mental distance—and even in today’s era of political polarization—there is minimal public controversy.4 Total ODA is currently around $200B annually (about 0.3% of donor country aggregate GDP) and has more than doubled in the last twenty years.

You could critique this ODA analogy too. Isn’t carbon removal “just” carbon removal, while ODA goes toward everything from health to education to food security and more? Is it plausible we’d spend similar or bigger sums on something much narrower? But this is very misleading. If we don’t spend on carbon removal—not only does carbon math change, but we’re effectively engaging in “anti-ODA” in the sense that we’re allowing horrific damage to the same set of human development interests that ODA seeks to improve. So carbon removal can easily be framed as a powerful and complementary development-aid investment. And, just like development aid itself is “an industry” with its own set of special interests and lobbies, spending on carbon removal will also create a whole new, geographically-distributed industry. In turn, that will make governments with industrial-policy and domestic-economy interests in carbon removal supply more supportive of multilateral procurement and compliance markets.

Who’s paying? Splitting the dinner bill between government and private sector

The first place people’s heads go in thinking about mid-century carbon removal demand is government spending—i.e., direct government procurement of removed tons from suppliers. This will almost certainly be one big part of the picture. The ODA comparison above shows that governments are able to sustain expenditures on things that don’t provide tangible benefits to citizens, and that expenditures can get quite large in absolute terms while still representing small fractions of overall government spending.

Yet in thinking about the source of demand, we should also be imagining a comparably significant role for private sector dollars. Voluntary markets won’t scale to the kind of levels we’re talking about, but compliance markets are already edging into the hundreds of billions. We can think of today’s largest compliance market—the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS)—as a ~$100B market currently.5 To be clear, the EU ETS is not a carbon removal market today; it’s a "cap and trade" scheme that limits company emissions and allows them to trade emissions rights. But it’s easy to imagine how this kind of compliance market progressively evolves into a carbon removal market as the supply of permanent removals ramps up.6

On the one hand, you could see today’s $100B EU ETS market as small relative to the ~$1 trillion carbon removal market size we’re contemplating by mid-century. But it’s much more encouraging when you take into account that:

What we ultimately care about is what compliance markets might look like across the globe, or at least across high-income countries. The EU ETS market size obviously comprises EU countries only; the EU’s GDP represents ~30% of OECD countries’ GDP and ~15-20% of global GDP, and other governments (e.g., UK, China, etc.) are already starting to move down the compliance-markets path.

Prices in the EU ETS and other compliance markets are rising, and rising fast. The numbers experts attach to the social cost of carbon have increased greatly as well. With compliance market prices already approaching $100/ton, the future target pricing we’re imagining for permanent carbon removal doesn’t look implausible at all.

The world gets wealthier

The Liebreich / Carbon Wrangler debate only considered this ballpark absolute number of a $200B carbon removal market. But what really matters is what aggregate mid-century spend on carbon removal is workable on a relative basis as a fraction of global GDP. It’s similar to ODA in that way; ODA would get a lot more contentious if it started eating up 2% or 10% of a country’s GDP.

How does a $1 trillion carbon removal market look with that lens? At current world GDP of ~$85 trillion, our hypothetical future carbon removal market would account for just over 1% of global GDP. But over the next 30 years, global GDP is projected to grow dramatically—more than doubling in real terms over that period.7 This has the effect of reducing by at least half (and possibly substantially more) the burden of carbon removal spending measured in relative terms.8 The chances are reasonably high that a $1 trillion market would constitute less than 0.5% of global GDP by mid century, bringing it into the same rough territory as today’s ODA.

Moments of historical plasticity

For the reasons outlined above, you can make a case that a $1 trillion carbon removal market doesn’t require too huge a ‘frame shift’ in spending patterns and priorities relative to today. But even if it does require some pretty honking changes, we shouldn’t get trapped in incremental, politics-of-today thinking. Consider this recent exchange Ezra Klein had with William MacAskill:

That molten-glass period in the immediate aftermath of World War II saw not only the creation of the United Nations but the dramatic buildup of the welfare state (particularly in Europe) and the birth of large-scale ODA.9 Both had precursors—such as European countries’ growing aid to their colonies in the interwar period—but the remarkable expansion after the war depended on the molten glass. Starting huge financial commitments like these isn’t easy, but once they’re established, it’s easy for the snowballs to grow further. They tend to ratchet.

Will we see molten-glass periods of plasticity in the next thirty years that might be relevant the plausibility of gigaton- and trillion-dollar scale carbon removal? On the one hand, we can’t say anything with certainty and the exact timing or triggers are impossible to predict. On the other hand, knowing what’s coming with climate change, humanitarian and biodiversity crises, and migration-fueled conflicts—against an existing backdrop of growing political polarization in many places—it seems hard to bet against earth-shaking moments of historical plasticity.

Concluding thoughts

Analytically, I can totally imagine looking at the prospects for a $1 trillion carbon removal market in the skeptical way Liebreich and others do. “Where is there any reliable evidence that enormous-scale government procurement is going to emerge? What’s going to trigger that change? We don’t even know if we can hit a reasonable price target and deliver at anything close to gigaton scale! Investors are crazy to bet big dollars on this right now.”

But—if we’re specifically asking whether a $1 trillion market is plausible—I think the answer has to be an emphatic yes.

Thinking forward from today’s infant stage market, you can see all these precursors coming into place, many of which didn’t exist a few years ago:

A billion-dollar advance market commitment in Frontier

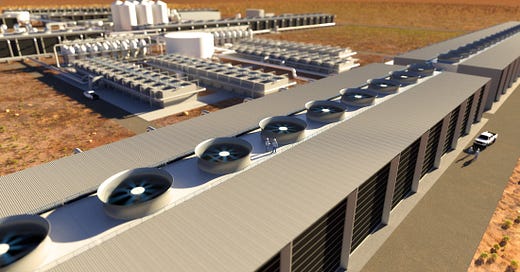

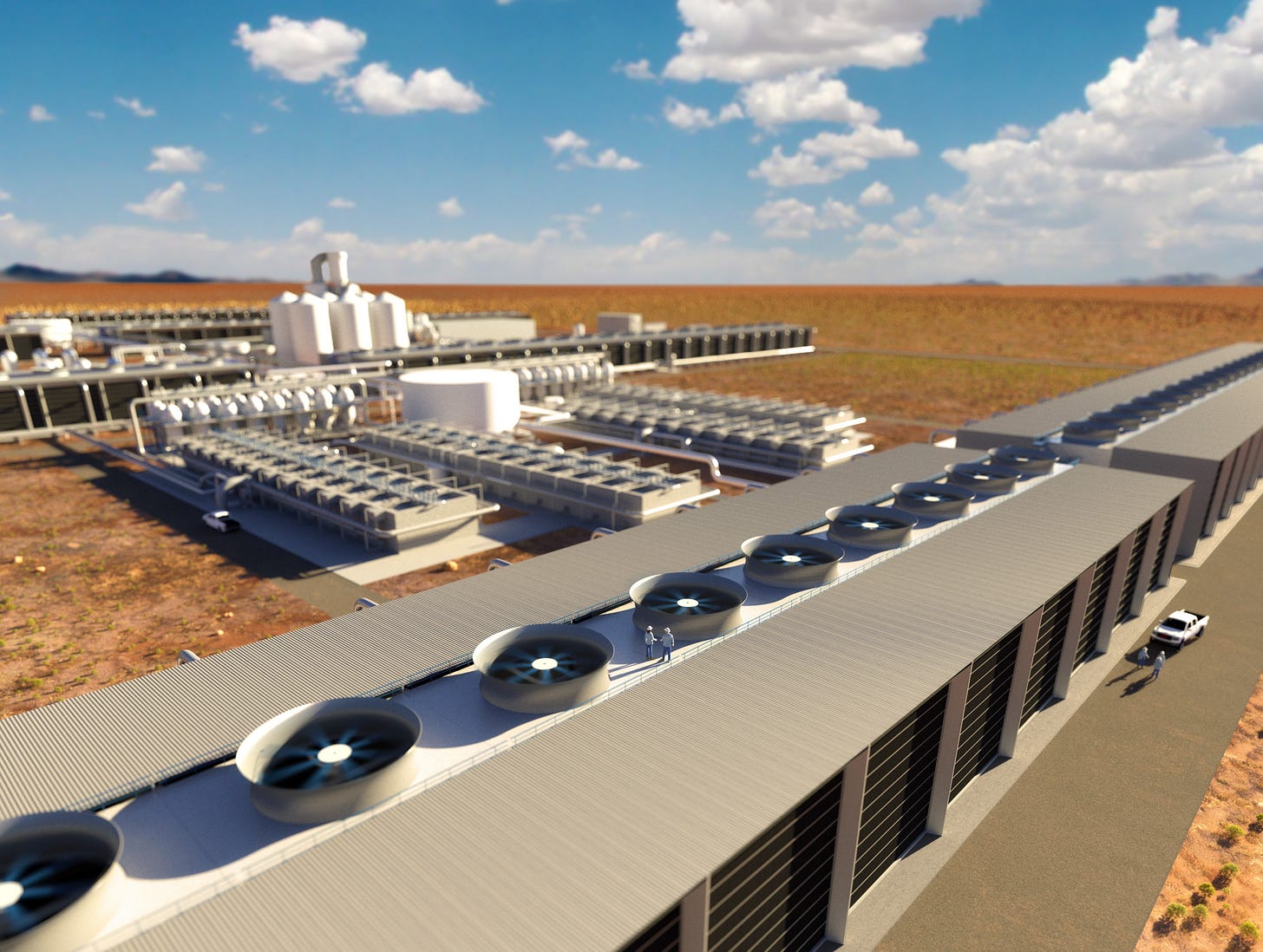

Generous subsidies and tax credits like 45Q (think of these as proto-procurement) that are changing the deployment curve as we speak (see, e.g., Project Bison, 1PointFive, Capture6, etc.)

The growth of compliance markets in the EU, UK and elsewhere

Movement toward state and local level government procurement of carbon removal

And as discussed above, thinking backward or downward from a $1 trillion market by mid-century, there are a handful of considerations that together make that magnitude seem much less daunting and/or effectively ‘haircut’ that number:

The 2X+ increase in global GDP, cutting the effective cost of carbon removal in half on a relative basis

The knowledge that carbon removal cost will be borne by both government and private sector, with neither needing to be the dominant source of funds

The not-unimaginable possibility that we achieve durable carbon removal costs well below $100/ton10

“Predictable unpredictable” Ministry-for-the-Future moments of historical plasticity that can dramatically shift the Overton window in the space of months or years

The world’s existing track record of spending 11- and 12-figure sums on priorities that share the diffuse/intangible-benefits profile of carbon removal

Whatever you make of this analytically, we also need to be thinking strategically and philosophically. Is the bigger danger what Liebreich fears—making claims that we can hit <$100/ton and deliver at gigaton scale in order to justify calls for aggressive investment in what could prove unworkable? Or is the bigger danger building a strong public narrative that gigaton-scale permanent removal is likely a fool’s errand and that we therefore shouldn’t invest aggressively—making it a self-fulfilling prophecy before we even really get going?

I believe the latter risk is the far bigger one. As Zeke Hausfather and others have emphasized, we have to start now if we want to get to what the IPCC says we need by mid century. We need to come out of the gate guns blazing. If we ask ourselves not just about market size but about scalability and cost targets, no-one knows. And there’s only one way to really find out.

Price-wise, there’s nothing magical about the $100/ton number: optically it’s attractive, and it’s a good stretch target for now, but it could easily wind up being off by 25% or 50% or more in either direction. The real questions are what is achievable from a cost perspective, what pricing levels future carbon markets will bear, how the future price of removal compares to the marginal cost of abating different sources of residual emissions at some future point, and so forth.

As far as volume, the real questions are how much removal will the world need just to achieve net zero by mid-century, and perhaps whether there is enough demand and supply to start dipping into net-negative territory (required in the second half of the century in scenarios that limit warming to the 1.5-2C range). This is outside my wheelhouse, but what seems clear is that—even just focusing on hitting net zero—a 2 gigaton volume feels at the low-ish end of the plausible spectrum of required removal scale. For a variety of reasons, that number could end up being higher, like 5 or 10 or even 20 gigatons. See e.g. this Nature paper and this great opinion piece by Zeke Hausfather and Jane Flegal.

The global market for vaccines is typically estimated to fall in the $40-60B range, though it’s worth noting that this includes both private and public spending. The global market size for waste management broadly defined is estimated at more than $1.6 trillion; most of that is industrial waste management, however, with household/municipal waste disposal making up a small fraction of the total.

Very often these private intermediaries are headquartered in the same country as the donor government. As an example, the US Agency for International Development might fund John Snow International (a large private USAID contractor based in Boston) to carry out a mobile-clinic HIV testing program in Cambodia, with the financial flow never passing through the coffers of the Cambodian government.

Even under Trump, threats to cut back on U.S. ODA were both moderate (~25%) and completely unsuccessful, with Congress sustaining aid levels at levels similar to the late Obama years.

While the EU ETS hit a reported $850B in market value last year, that reflects total trading volume—with any given allowance often being traded back and forth multiple times. If we just isolate the allowances issued (1.35 GtCO2) at an average price of roughly $80/ton, we get a market size just over $100B (h/t Romain Lacombe).

There are different ways to force companies to bear the social cost of emissions—including direct carbon taxes, cap-and-trade schemes, and compliance markets with companies buying removals instead of emissions rights, etc. For our purposes here, the main point is that government procurement of carbon removal funded out of general revenues can be supplemented with financial responsibility specifically imposed on emitters, whether those companies then do the buying of removed tons themselves or pay the government or other third party to do the buying.

See example projections and discussions here (PwC) and here (OECD) and here (Center for Global Development). It's worth noting that quite a few of today's developing countries (especially the largest or fastest-growing middle-income countries like Indonesia, India, etc.) will represent a much higher fraction of GDP by mid century. And you can argue that these countries will or should contribute relatively less to carbon removal procurement than today's wealthy countries that are responsible for most emissions to date. At the same time, these rising economies will (by definition) be getting wealthier themselves and accounting for a rising share of emissions, and many of them will have domestic carbon removal industries. So they are unlikely to be sitting on the sidelines entirely when it comes to buying carbon removal or expanding compliance markets domestically.

The US defense budget is an interesting case study in the sometimes surprising dynamics of absolute vs relative spending. There is a strong and accurate public narrative that the defense budget (now ~$800B annually) is huge, bloated and generally only goes up over time, if we smooth out war-and-peacetime bumps. What is simultaneously true is that defense spending has consistently shrunk over time as a fraction of GDP and government spending—from >8% in 1960 to <4% today.

Liebreich also expressed strong skepticism about permanent carbon removal achieving levels of $100/ton or below. But betting against that isn't a low-risk bet. Generally, the history of the learning and cost curves for things of this ilk consistently surprises us (even experts) in just how low costs can go—think solar, HIV drugs, lithium ion batteries, and more. And just as importantly, you’re not betting against a single technology (e.g. liquid sorbent DAC) nor even against a class of technologies (e.g., DAC) but against a whole suite of carbon removal avenues current and as-yet-uninvented.

I have a different take on the road ahead.

1. We're seeing an acceleration in climate calamities, both in frequency and scale. This means that the leisurely deadline of 2050 is too late and that 2030 is more likely.

2. We've seen that governments do not act in response to human tragedy (e.g., destruction of Bahamas, deadly heat waves in India, etc), despite it being increasingly prevalent. This leaves economic dislocation and political pressure (in democracies) as the pressure points.

3. With economies as the only point in common between countries, I predict that the international agreement needed for meaningful action will only come after a severe dislocation of the global economy. A climate-induced recession. It has to be undeniably climate-related and it has to be painful.

4. A panicked response will follow, with massive government intervention. Grid electrification will explode, but it will take time to be completed. A global carbon market will develop because every country will mandate emission reductions, by agreement. It has to include every country and every economic system, and not include subsidies that give one country an unfair advantage. It will take time to be worked out: my bet is that it will come into effect by 2028-2030.

5. We need to be ready with solutions by then. This gives us a six year head start.

Good luck to us all.

Hello Dai (and others),

-1- Txs for the interesting article, it clearly gives some depth into the discussion of @carbonwrangler and @mliebreich.

-2- As you explained "'It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future'” .

Who would even imagined the cost reduction of solar. Or the currently happening rise of Electric cars (except @ProfRayWills and @chrisnelder )

-3- Now to CO2 removal.

3.1. There will be cost reduction.

3.2. Quite often there are more advantages (besides the CO2). See Project Vesta.

The plan was anyway to perform a beach nourishment project. So why not do it with sand (and my prediction that there will be even another advantage)

https://www.vesta.earth/southampton

3.3. The more solar/wind (and nuclear) are scaling up, the less we need it. But in a net zero world we need (some) CO2 removal.

CO2 reduce, re-use and remove.

Pol Knops